Summary:

This Book is For:

- People who are interested in the causes of conflict, and learning how to transform them into a force of unity.

- Individuals who want to attain greater self-knowledge, specifically when it comes to their desires, and who are striving for greater authenticity.

- Parents and teachers who want to learn how to better models for their children and students.

- Basically: human beings alive on this planet.

It's surprising how little that people know about where their desires actually come from. It's not obvious why we want what we want, and it's the endlessly fascinating "universe of human desire" that is the subject of today's book.

Backed up by the hugely influential French intellectual René Girard, author Luke Burgis shows that humans rarely desire anything independently. Human desire is mimetic - we imitate what other people want.

But in the exact same way that gravity exerts an invisible force on our bodies, the psychological force of mimesis shapes human desire all the time, silently and invisibly, and hardly anyone is aware of it happening at all.

Wanting is about how we arrive at our desires, and about how we can transform our relationship with those desires in order to step into our full humanity, relate to each other more harmoniously, and intelligently select our desires in such a way that we enlarge ourselves, rather than diminish ourselves.

Burgis packs a ton of ideas into a relatively short book, but once you start to see what he's talking about, you can't unsee it. Desire is like the water that the fish are swimming in, and Wanting takes us beyond the fishbowl to view the drama of desire from above.

Among other things, he shows how the epic automotive rivalry between Enzo Ferrari and Ferruccio Lamborghini was driven by mimesis, until one of them put an end to the mimetic crisis; he tells the story of how a brilliant ad executive from the turn of the century was able to tap into mimetic forces and get thousands of women hooked on smoking; he examines why Ivy League students all tend to pick the same majors; why certain goals are attractive to some and not to others; and outlines the horrifying history of mimesis and scapegoating.

There's so much here to get into, but the common theme is not that desire or mimesis is somehow "bad" - or that it can even be overcome - but that we can train ourselves to desire differently, and to attain some measure of control over what we want and why we want it. It's an extremely liberating book in many ways, and since the future is going to be shaped by our desires, it's crucially important to understand where they came from today.

Key Ideas:

#1: “Each of us spends every moment of our life, from the moment we’re born to the moment we die, wanting something. We even want in our sleep. Yet few people ever take the time to understand how they come to want things in the first place. Wanting well, like thinking clearly, is not an ability we’re born with. It’s a freedom we have to earn.”

The human universe of desire is a lot like the water that fish are swimming in. It's not obvious, especially if you aren't looking for it, how our desires are modeled and reflected back to us by the people we surround ourselves with - and by the people we are exposed to. But, we really have to become aware of it if we're going to earn a very important freedom: the freedom to be in relative control over our own desires.

Nobody really thinks that they need to learn how to "want well," but upon closer inspection, you can see that we're at the mercy of unexamined forces that we've never learned how to appreciate and harness. We think, "Of course I know what I want! I chose it!" but the wider picture is much more interesting and fluid.

When it comes to mimesis and modeling, we're always doing it, so we really only have the choice between doing so well or poorly. We can't escape the psychological dynamics of mimesis (without living under a rock), so we may as well get good at it. That's one of the biggest takeaways from Wanting: we have to earn our freedom from unexamined mimesis and the wrong turns that it can cause us to make.

#2: “The imitation of desire has to do with our profound openness to other people’s interior lives – something that sets us apart as humans. Desire, as Girard used the word, does not mean the drive for food or sex or shelter or security. Those things are better called needs – they’re hardwired into our bodies. Biological needs don’t rely on imitation. If I’m dying of thirst in the desert, I don’t need anyone to show me that water is desirable. But after meeting our basic needs as creatures, we enter into the human universe of desire. And knowing what to want is much harder than knowing what to need.”

#3: “Desire doesn’t spread like information; it spreads like energy. It passes from person to person like the energy between people at a concert or political rally. This energy can lead to a cycle of positive desire, in which healthy desires gain momentum and lead to other healthy desires, uniting people in positive ways; or it can become a cycle of negative desire, in which mimetic rivalries lead to conflict and discord.”

Some people make better models than others. Mimetic desire "unites people in a shared desire for some common good," but it can also lead to rivalry and conflict. Healthy behaviors and ways of relating can come about through mimesis, of course, as in a work culture that is based on accountability, autonomy, and "assumed positive intent" in communication. But picking the wrong models, even or especially unconsciously, can be disastrous.

This works on a larger scale as well, when "people want something that they couldn’t imagine wanting before – and they help others go further, too.” For example, a model like Simone Weil can show us admirable ways of relating and listening to other human beings, and a model like Naval Ravikant can also show us how to intelligently select our desires. Then there are more innocuous models like the people who influence how we dress and hold our coffee cups, for example. We're always receiving cues about how to behave from those around us.

As mentioned previously, there are also negative cycles of mimesis, leading directly to rivalry and conflict. As Burgis explains, most conflicts don't arise because people want different things, but because they want the same things. It develops from a scarcity mindset that says there isn't enough to go around, and "If that person gets what they want, then I won't get what I want." In a world of expanding abundance, this view is becoming increasingly less defensible.

#4: The Romantic Lie, explains Burgis, is the common belief that we are the original source of our own desires and that we have full agency over the formation of our goals and plans. It's the assumption of independence, whereas the reality is that we are embedded in a network, and we select desires based on what our models mirror back to us. They function in the same way as someone standing up ahead in the road, pointing us in the direction of something we can't yet see.

The reality behind the Romantic Lie is much different, and we are influenced by our models to a much more significant extent than we may be comfortable admitting. This goes toward explaining many features of modern life, such as the fact that in Ivy League universities, most students eventually converge on the same few careers, such as finance, consulting, medicine, etc. You could study anything! You could be anything, follow any curiosity or intellectual gravity-pull, but you decide to do the same thing as a thousand of your peers. Why? Mimesis.

#5: We are inextricably linked in networks of desire and mimesis, but human beings are also necessarily hierarchical in nature - there is always a hierarchy of desires upon which we are basing our choices. We want some things more than we want other things, and this is because of our underlying values.

We are always choosing based on what we implicitly or explicitly believe, and the crucial insight here is the importance of becoming aware of that. Values tell us what to pay attention to, and if you haven't carefully delineated - even if only for yourself - what is most valuable, you will be vulnerable to being pulled in all these different directions that may not actually be best for you.

In the book, Luke Burgis tells how at Zappos, the shoe company, they experimented with a flat leadership structure and everything nearly fell apart. Nobody knew what the structure was: what was important, who they should pay attention to, which behaviors and goals they should adopt. They were adrift, and almost literally couldn't function.

#6: Imitation differs in kind and quality depending on where it happens – depending on whether it happens in what Burgis calls “Freshmanistan” or “Celebristan.” Both metaphorical places have different consequences when it comes to what we want.

Freshmanistan consists of the people we are closest to, either geographically or socially. It’s like being a freshman in high school and having to differentiate yourself from people who are all fairly similar to you. It’s also usually the people just one or steps above us that we tend to be jealous of, not the people in Celebristan who are so far ahead of us that they aren’t really our competition.

Models in Celebristan – Hollywood actors, business moguls, saints, etc. – are external mediators of desire, in that they are operating outside our personal sphere. We aren't personal friends with them, we don't represent serious competition for the status that they've claimed, and we just don't feel the gravitational pull that we do from the people who are closest to us.

Rivalry is a function of proximity, and it's much harder to be jealous of someone who's a billionaire than it is to resent the person in the same office, doing the same type of job, earning just a few thousand dollars more. Sounds crazy, but it's true.

#7: When large groups of people all want the same thing, there's a danger of a mimetic crisis emerging. As explained above, rivalry is a function of proximity, and it's the people who want different things who can usually just go their own way in peace.

When mimetic crises do emerge, people often look for a scapegoat, someone different, an outsider on whom they can pin the blame for what went wrong in their mimetic universe.

In the book, a fictional example is taken from a pool party that ends in disaster. A large group of people are partying in a pool, and for whatever reason, an electronic stereo (what other kind is there?) falls into the pool, causing everyone in the pool to receive an electric shock.

Everyone inside the pool looks for some cause, someone who's at fault, and they all settle on the one guy who's just returning from the house after grabbing a beer from the fridge. The guy had nothing whatsoever to do with the stereo falling into the pool at all! It's just that there's a mimetic crisis, someone needs to be at fault, and so they settle on an outsider, someone to ostracize.

This is a process that has been playing out for thousands of years, and even the word ostracize comes from the ancient Greeks. When a decision was at hand whether to exile a certain individual, the citizens would cast their votes on broken pieces of pottery called ostraka, and if that person received enough votes, they would be exiled for ten years.

#8: “History is the story of human desire.”

You don't have to look far to notice the impact that desire and mimesis have had on historical events. Even novels are primarily driven by mimesis - at least good novels are - with the drama propelled by the interplay between the desires of all the main characters. Creative writing teachers often advise their students to ask themselves what it is that their characters want, and to let the answers to that question drive the action.

Through the lens of desire isn't the only way to look at human history, but it gives an enlightening glimpse into events and motivations and decisions that may seem mysterious and opaque when you don't consider the powerful impact of desire and mimesis.

#9: “There are always models of desire. If you don’t know yours, they are probably wreaking havoc in your life.”

This comes back to the fish swimming in water without realizing it. It's possible to live one's whole life being blissfully unaware of the role of mimesis in one's decisions, but you'll be empowered to make much better choices in your life if you do bring it into conscious awareness.

It's probably impossible to be completely anti-mimetic (and why would you want to be?) but acknowledging your models of desire can only be a good thing. You will always be influenced by what the people around you are modeling, but you'll have some measure of control over this process, and be able to bring your full humanity into the arena of your choices, instead of just being carried along on the whims of others.

Once you see mimesis, you can't unsee it. You will still have the same basic human needs, but your desires will likely be more conscious. As Abraham Maslow has said, it's not obvious what we should want. It's actually one of the rarest psychological achievements to have figured this out.

#10: “We are generally fascinated with people who have a different relationship to desire, real or perceived. When people don’t seem to care what other people want or don’t want the same things, they seem otherworldly. They appear less affected by mimesis – anti-mimetic, even. And that’s fascinating, because most of us aren’t.”

This calls to mind the 48 Laws of Power, by Robert Greene, and how we can use these ideas either for "offense" or "defense." You can use the idea of mimesis - or, in this case, anti-mimesis - as a defense against people who would influence your desires to further their own aims. Or you could consciously strive to be more anti-mimetic, and thereby make people more fascinated by you.

It's true: when you run into someone who doesn't want what the rest of us want, they seem much more powerful. Someone who actually doesn't care about what they've been trained to want? It lends them an air of mystery, fascination, excitement.

What could you offer this person? What drives them? Uncontrollable and unpredictable is scary - like they're not playing the same game - and it automatically confers an otherworldly aura on the person who can successfully cultivate it.

#11: “The danger is not that we have a slot machine in our pockets. The danger is that we have a dream machine in our pockets. Smartphones project the desires of billions of people to us through social media, Google searches, and restaurant and hotel reviews.

The neurological addictiveness of smartphones is real; but our addiction to the desires of others, which smartphones give us unfettered access to, is the metaphysical threat.

Mimetic desire is the real engine of social media. Social media is social mediation – and it now brings nearly all of our models inside our personal world. We live in Freshmanistan. Each of us has to examine what this means in our life – how mimetic desire manifests itself in the circumstances we’re in, and how we should live.

This new world represents a threat but also an opportunity. Which new pathways of desire will emerge? Which new opportunities can we seize? How can we infect and be infected by desires that will ultimately lead to fulfillment and not to destruction? These are the questions that we’ll finally have to ask and answer as individuals, and as a society.”

Book Notes:

“Desire, like gravity, does not reside autonomously in any one thing or person. It lives in the space between them."

“Tony didn’t look like a guy who had millions. He had sold the first company he co-founded, LinkExchange, to Microsoft for $265 million in 1998 at the age of twenty-four. But he dressed in plain jeans and a Zappos T-shirt and drove a dirty Mazda 6. Within a few weeks of hanging out with him, I ditched my True Religions (I know) and started shopping at the Gap. I began to wonder if I should drive an older and dirtier car.”

"It's not irrational. It's mimetic."

“You can never be a neutral observer of mimetic desire.”

“By the way, did you know that in almost every language in the world, people fall in love? Nobody rises up into it.”

“Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is too neat. After a person has fulfilled their basic needs, they enter a universe of desires that does not have a stable hierarchy.”

“Facebook was built around identity – that is to say, desires. It helps people see what other people have and want. It is a platform for finding, following, and differentiating oneself from models. Models of desire are what make Facebook such a potent drug.

Before Facebook, a person’s models came from a small set of people: friends, family, work, magazines, and maybe TV. After Facebook, everyone in the world is a potential model.

Facebook isn’t filled with just any kind of model – most people we follow aren’t movie stars, pro athletes, or celebrities. Facebook is full of models who are inside our world, socially speaking. They are close enough for us to compare ourselves to them. They are the most influential models of all, and there are billions of them.

Thiel quickly grasped Facebook’s potential power and became its first outside investor. ‘I bet on mimesis,’ he told me. His $500,000 investment eventually yielded him over $1 billion.”

Equality is good. Sameness is generally not—unless we’re talking about cars on an assembly line or the consistency of your favorite brand of coffee. The more that people are forced to be the same— the more pressure they feel to think and feel and want the same things— the more intensely they fight to differentiate themselves.

“Models are most powerful when they are hidden. If you want to make someone passionate about something, they have to believe the desire is their own.”

“Naming the mimetic forces at work in the systems in which we operate is an important first step toward making more intentional choices.”

“Eve originally had no desire to eat the fruit from the forbidden tree – until the serpent modeled it. The serpent suggested a desire. That’s what models do. Suddenly, a fruit that had not aroused any particular desire became the most desirable fruit in the universe. Instantaneously. The fruit appeared irresistible because – and only after – it was modeled as a forbidden good.

We are tantalized by models who suggest a desire for things that we don’t currently have, especially things that appear just out of reach. The greater the obstacle, the greater the attraction.”

“Isn’t that curious? We don’t want things that are too easily possessed or that are readily within reach. Desire leads us beyond where we currently are. Models are like people standing a hundred yards up the road who can see something around the corner that we can’t yet see.

So the way that a model describes something or suggests something to us makes all the difference. We never see the things we want directly; we see them indirectly, like refracted light. We are attracted to things when they are modeled to us in an attractive way, by the right model. Our universe of desire is as big or as small as our models.”

“After all, each of us is a highly developed baby.”

“What happens in a mob happens in a fog.”

“The first stone is the only stone without a mimetic model.”

“For more than twelve years, tens of millions of Americans watched the same TV show. Battle lines were drawn at the beginning of each episode. Every person on the show wants the same thing: the prestige of being proclaimed the victor, which will earn them praise from an authority figure and, with it, the adulation of the masses. And each of them is willing to do nearly anything to get it.

They fail. They engage in finger-pointing, backstabbing, and betrayals. Then, when the game is over, they walk into a giant boardroom. Donald Trump is seated, scowling, at the middle of a long table. They all want to be his next apprentice, but only one can win. Trump lets the mimetic crisis escalate until it’s boiling over.

Finally, he points a finger at one of them and says, ‘You’re fired!’ The crisis is averted. The scapegoat goes home. The team can get back to business. Meanwhile, the perception of Trump as a mimetic model – a person who knows what he wants – grows stronger every time he points his finger and utters the words, ‘You’re fired.’ After a dozen years of Trump cultivating and cementing his status as the ‘master’ and everyone else as the ‘apprentice,’ it’s not surprising that he became a cult-like figure.”

“Having a scapegoat means not knowing that we have one.”

"Before I can tell my life what I want to do with it, I must listen to my life telling me who I am.”

-Parker Palmer

“A good leader never becomes an obstacle or rival. She empathizes with those she leads and points the way toward a good that transcends their relationship – shifting the center of gravity away from herself.”

Empathy disrupts negative cycles of mimesis. A person who is able to empathize can enter into the experience of another person and share her thoughts and feelings without necessarily sharing her desires. An empathetic person has the ability to understand why someone might want something that they don’t want for themselves. In short, empathy allows us to connect deeply with other people without becoming like other people.

“The future will be a product of what people want. The things we build, the people we meet, and the wars we fight will depend on what people will want tomorrow. And that starts with the way that we learn to want today.”

“The question ‘What do we want to want?’ is unsettling partly because, in a world of engineered desires, we have to wonder who is doing the engineering. But also because the question implies that it’s possible to want to want something, yet not be capable of wanting it. We cannot want what we lack a model for. The model that we adopt for the future is critical to the formation of our desires.”

Important Insights from Related Books:

Scapegoat, by Charlie Campbell:

“In the beginning there was blame. Adam blamed Eve, Eve blamed the serpent, and we've been hard at it ever since."

“There are essentially two types of modern or post-ritual scapegoats: those created unconsciously, as an expression of our rage and incomprehension, in whose guilt everyone believes; and those created as a conscious act, by those seeking to deflect blame away from themselves."

“The only real conclusion that can be drawn from this long history is that scapegoating doesn't work. All too often it covers up the problem, rather than solving it; it focuses on rotten apples when really it is the barrel that is disintegrating around them, and it results in an incredibly harsh treatment of a minority.

The most it can ever achieve is a temporary lessening of the problem, but the real roots remain. Maybe we do need some form of purification ritual, some way of allowing ourselves to forgive ourselves and move on after disaster, but this can't be it."

This Book on Amazon: Scapegoat, by Charlie Campbell

Spent, by Geoffrey Miller:

“I started to see that marketing underlies everything in modern culture in the same way that evolution underlies everything in human nature.”

“Basic survival goods are cheap, whereas narcissistic self-stimulation and social-display products are expensive. Living doesn’t cost much, but showing off does.”

“We’re seldom honest with ourselves about why we buy things, and advertising euphemisms don’t help. Which slogan sounds better:

‘L’Oreal: Because you’re worth it,’

or:

‘L’Oreal: Because you want to look younger than the skanky Starbucks barista who’s always flirting with your husband?’

How about these:

‘The 2006 BMW 550i: Poised for performance,’

or:

‘The 2006 BMW 550i: Poised to leave burning tire smoke in the spotty faces of those Subaru-WRX-driving punks who threaten your masculinity as a divorced 47-year-old orthodontist.’”

This Book on Amazon: Spent, by Geoffrey Miller

The Laws of Human Nature, by Robert Greene

"People are generally dealing with emotions and issues that have deep roots. They're experiencing some desires and disappointments that predate you by years and decades. You cross their path at a particular moment and become the convenient target of their anger or frustration. They're projecting onto you certain qualities they want to see. In most cases, they're not relating to you as an individual."

"The greatest danger you face is your general assumption that you really understand people and that you can quickly judge and categorize them. Instead, you must begin with the assumption that you are ignorant and that you have natural biases that will make you judge people incorrectly. The people around you present a mask that suits their purposes. You mistake the mask for reality.

Let go of your tendency to make snap judgments. Open your mind to seeing people in a new light. Do not assume that you are similar or that they share your values. Each person you meet is like an undiscovered country, with a very particular psychological chemistry that you will carefully explore. You are more than ready to be surprised by what you uncover. This flexible, open spirit is similar to creative energy - a willingness to consider more possibilities and options. In fact, developing your empathy will also improve your creative powers."

"The first step, then, is the most important: to realize you have a remarkable social tool that you are not cultivating. The best way to see this is to try it out. Stop your incessant interior monologue and pay deeper attention to people. Attune yourself to the shifting moods of individuals and the group. Get a read on each person's particular psychology and what motivates them. Try to take their perspective, enter their world and value system.

You will suddenly become aware of an entire world of nonverbal behavior you never knew existed, as if your eyes could now suddenly see ultraviolet light. Once you sense this power, you will feel its importance and awaken to new social possibilities."

Read the Full Breakdown: The Laws of Human Nature, by Robert Greene

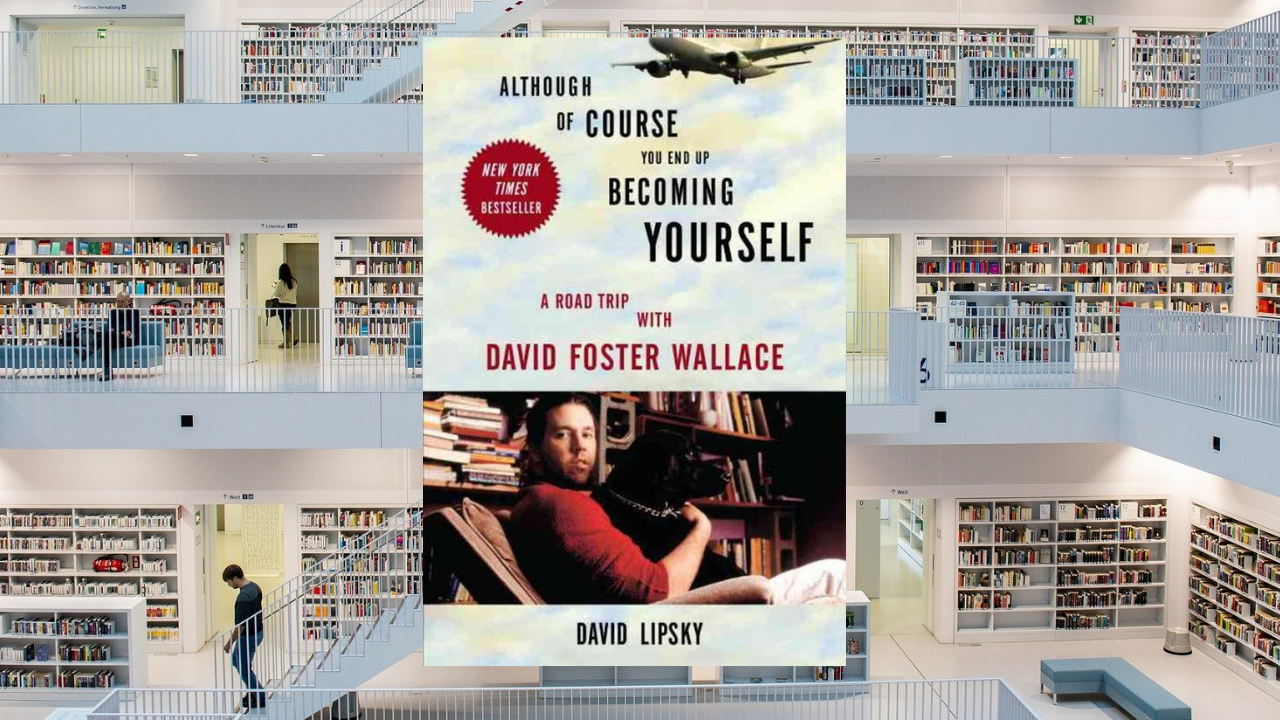

Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, by David Lipsky

“It’s more like, if you can think of times in your life that you've treated people with extraordinary decency and love, and pure uninterested concern, just because they were valuable as human beings.

The ability to do that with ourselves. To treat ourselves the way we would treat a really good, precious friend. Or a tiny child of ours that we absolutely loved more than life itself. And I think it's probably possible to achieve that."

“Like, at a certain point, we're gonna have to build some machinery, inside our guts, to help us deal with this. Because the technology is just gonna get better and better and better.

And it's gonna get easier and easier, and more and more convenient, and more and more pleasurable, to be alone with images on a screen, given to us by people who do not love us but want our money.

Which is all right. In low doses, right? But if that's the basic main staple of your diet, you're gonna die. In a meaningful way, you're going to die."

“And I think that the ultimate way you and I get lucky is if you have some success early in life, you get to find out early it doesn't mean anything. Which means you get to start early the work of figuring out what does mean something."

Read the Full Breakdown: Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, by David Lipsky

The View from the Opposition:

No one's ideas are beyond questioning. In this section, I argue the case for the opposition and raise some points that you might wish to evaluate for yourself while reading this book.

#1: Anti-mimesis can shade into mindless non-conformity.

There's a point of diminishing returns when it comes to being anti-mimetic, or being resistant to the imposed desires of others. At a certain point, it's just being different for the sake of being different, regardless of whether the crowd might actually have the right idea.

It calls to mind those ads on TV or the subway that tell you to "think different," or "be an outsider," etc. If you think about it for a few seconds, you can see that the only way those companies can afford to take out those ads is if they're hooking in thousands of people! They're all buying the same product, but they're each being sold the idea that that's not true.

The larger point is that there are times when the crowd is absolutely correct, and you should follow their pronouncements! General politeness, wearing pants in public, common courtesy - these are all examples of social conditioning that serve us well.

#2: Knowing all this, it's still extremely hard to see.

Don't think that just because you read a book on mimesis, suddenly you'll be able to choose your own desires in every single situation, with full awareness of what you're doing. We all slide back into our old patterns, at least occasionally, and most of the mimetic effects we've been exposed to our whole lives have been completely unconscious. To expect all this to change after reading a single book - or a breakdown of that book - is unrealistic.

In fact, if it makes you feel any better (and I hope it does!), the Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and economist Daniel Kahneman says that he still falls prey to many of the cognitive biases that he's spent his entire career studying. So even the guy who received a Nobel Prize for piercing veils of illusions still sometimes falls victim to those illusions as well!

#3: The eternal feminine draws us onwards and upwards.

The line is from Goethe, if you were wondering! And even if you weren't wondering, it's still from Goethe. Anyway, I mean to say here that I don't think Burgis lays enough emphasis on the role of evolutionary psychology, competition, and mating when it comes to human desire.

Much of what we desire is because it makes us look attractive to potential mates, and I don't think that this was explicitly laid out in the book. Men do crazy things to attract women - and vice versa of course - and a big part of that is conspicuous consumption, buying patterns, signaling, and displays of value. I think it's under the surface of what Burgis was saying, but it's so important to understanding the human universe of desire that I wanted to lay it out explicitly here.

"The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

-F. Scott Fitzgerald

Action Steps:

So you've finished reading the book. What do you do now?

#1: Retreat into silence (temporarily).

Silence can be wonderful for getting in touch with your deepest desires and reconnecting with your core self. So set aside some time - ideally every day - to sit in quiet reflection, away from the mimetic noise pollution of the modern world, and think about what it is that you actually want. Make this a habit, and keep returning to yourself as a base from which to explore your desires and reflect on your relationship with desire itself.

#2: Name your models.

The first step toward intelligently selecting your desires is to become conscious of who is shaping them now. In Freshmanistan this is especially hard to do, as our influences and models are generally hidden. But it's worth taking even the smallest tic or mannerism and asking yourself where it came from.

Speaking for myself, I notice that there's a specific way of sitting at the dinner table that I've taken from my father, and that certain phrases I use all the time come from a few particular individuals that I spend a lot of time with. Untangling the web of desires isn't going to be fast or easy - and you probably won't get to the bottom of all of them - but it's an enlightening exercise to say the least.

#3: Distance yourself from unhealthy models.

Once you've named your models, you can start moving away from the destructive ones. None of this is going to be easy! Especially if some of your current models are people you see all the time, are related to, or feel a strong connection with. But if their gravitational pull isn't leading you to where you want to go, then you really must separate yourself from them. Think of the people in your life as the driver of the car that you're in: do you really want to be in the back seat with them at the wheel?

#4: Develop at least one "thick" desire.

Thin desires are desires that aren't especially good for you, that don't lead to any deeper sense of fulfillment, and that are distractions from the kind of life that you could be living if you were to devote yourself to developing thick desires instead.

Thick desires are desires that nourish you - that have enough "calories" in them to sustain you - and that lend meaning and significance to your life. For some people, getting drunk every weekend would be a thin desire, whereas choosing to have a child would be a thick desire. There are endless permutations and interpretations, of course, but it's worth spending a lot of time figuring this out.

#5: Live like a model.

Live as though you have a responsibility for shaping what other people want. Because you do! You are embedded in a network of relationships and tangles of desire, and you are a model for others in exactly the same way that they are a model for you.

So you have an ethical obligation to model thick desires and to help make them seem attractive to others as well. People are watching; they are waiting to catch signals from you and to receive guidance from you, and we are all counting on you to learn how to desire well.

About the Author:

Luke has co-created and led four companies in wellness, consumer products, and technology. He’s currently Entrepreneur-in-Residence and Director of Programs at the Ciocca Center for Principled Entrepreneurship where he also teaches business at The Catholic University of America.

Luke has helped form and serves on the board of several new K-12 education initiatives and writes and speaks regularly about the education of desire. He studied business at NYU Stern and philosophy and theology at a pontifical university in Rome.

He’s Managing Partner of Fourth Wall Ventures, an incubator that he started to build, train, and invest in people and companies that contribute to a healthy human ecology. He lives in Washington, DC with his wife, Claire.

Additional Resources:

How Social Media Has Made Us All Rivals

The Barbell Shape of Modernity

This Book on Amazon:

If You Liked This Book:

Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, by Rene Girard

I See Satan Fall Like Lightning, by Rene Girard

Rene Girard's Mimetic Theory, by Wolfgang Palaver

Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World, by Rene Girard

The Laws of Human Nature, by Robert Greene

Finite and Infinite Games, by James P. Carse

The Status Game, by Will Storr